Who has the Right to the City?

“The right to make and remake ourselves”

This is a quote that resonated with me from our discussion with collegiate peers at different universities. It puts to simplest terms my definition of a right to the city: the collective ability of the community to shape urban processes. This includes an equitable right to culture, urban housing justice, and access to resources.

Why does this matter? In class, we are learning about the consequences of the historical exclusion of Black communities from these rights due to spatial racism and the system of American Apartheid. By binding individuals and ethnic groups with a specific geographical location and then arranging them in a hierarchy in spatial terms, there is a consequential hypersegregation. As described in The Black Butterfly by Lawrence T. Brown as American Apartheid, the Black Butterfly “describes the geographic clustering of where Black Baltimoreans live” and “also a political, an economic, and sociocultural description”. In direct contrast, the White L is a “description of the geographic clustering where White Baltimoreans live” and is also “where access to capital is most readily available”, creating structural advantages. This can be seen through the racialized access to food in the system of food apartheid within the Black Butterfly. As many grocery stores are concentrated in the wealthier White L. to gain the most profit, there is a lack of healthy and accessible food in low-income areas, like the Black Butterfly. Without proper nourishment, there is a direct impact on the health and livelihood of people living in these areas. The lack of food sovereignty, however, is just one of the many systems that have historically disenfranchised African American communities.

“Where eminent domain is being used is in the Black neighborhoods and so, our history is being erased.”

This quote from the article titled Black Neighborhoods Matter by the Baltimore Beat describes the issue of serial forced displacement. Community leader Sonia Eaddy calls Poppleton, a neighborhood in the Black Butterfly, her home and roots. However, when the private development company from New York City, La Cite, planned to ‘upgrade’ Poppleton by clearing all of the existing homes and replacing them with newer and more expensive housing units backed by the Poppleton Urban Renewal Plan, Ms. Eaddy, and her fellow community members were at risk of losing their homes. So although redevelopment may sound nice, the forced uprooting of the Poppleton community would leave many residents displaced with very little compensation.

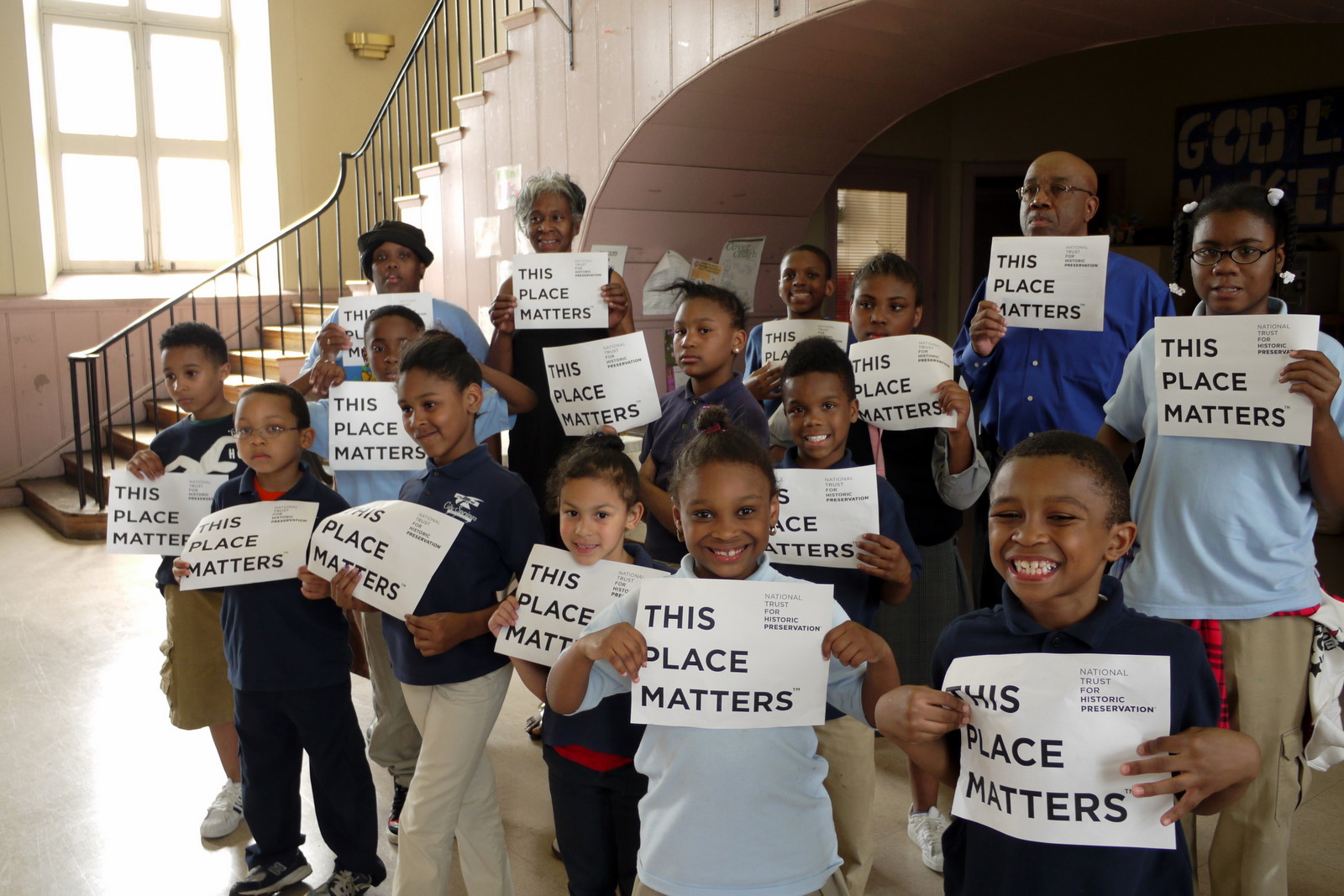

What’s at stake? To be honest, I did not realize what truly was at stake until I met Ms. Sonia Eaddy at the Baltimore History Unconference last weekend. While talking about the struggle she had to go through to win her eminent domain lawsuit, there were many times her voice broke down and you could visibly see the trauma of her experience. There was a moment when Ms. Betty Bland-Thomas, community leader of Sharp Leadenhall, another neighborhood in danger of urban renewal, held Ms. Sonia as she was struggling to speak. Although in class we have been analyzing the issues they were discussing, it was not until then that I really understood that these are actual lived experiences. The implications of these urban renewal plans destroy lives, families, and communities. There is history in these homes that deserves to be preserved. Nobody deserves to have their homes, their roots taken from them, especially for capital gains. The right to the city must be instilled in praxis so communities, like those in Poppleton, can actually create and live in a city that feels like home.

After two decades of fighting, Ms. Sonia Eaddy along with the help of community members and academics finally achieved ‘victory’. While she didn’t save her entire block, she saved her house from being demolished. However, Sonia explains that “her fight is not over. She has a bigger foe ahead of her than a developer or even the city of Baltimore: harmful eminent domain laws. She says that these laws are used to steal not just Black homes, but Black lives and Black histories”.

New Project Ideas

One of the coolest experiences I had at the Baltimore History Unconference was meeting a public access archivist for Afro-Charities. Kendal, Aziza, and I happened to sit next to her at lunch, and she told me that she had done her military service in Korea, sparking her interest in researching Korean-American communities in Baltimore. As a second-gen Korean-American, learning about the Korean community and how we contribute to culture and race relations is a subject I hold very close to my heart. I was so excited to meet someone who knew about the Korean-American community in Baltimore since I only really know about the Korean-American communities in New York City and Montgomery County. She sent me alot of resources that tied in with my idea of interviewing people in the city of Baltimore. I now know of people I am considering interviewing! From rice-cake shop owner Jae Won Kim, MICA artist Mina Cheon, and other community members, I hope to use the interpersonal medium of conversation and interviews to share the stories of Korean-American individuals. Being the second largest population of people of color in 2000, I believe Koreans should be mentioned when discussing Baltimore's history and community relations.

Comments

Post a Comment